Cody Yellowstone Uncovered

Read our travel blog for tips, tricks, hidden gems, and fascinating facts — all here to help you prepare for your unforgettable trip to wild Cody Yellowstone, Wyoming.

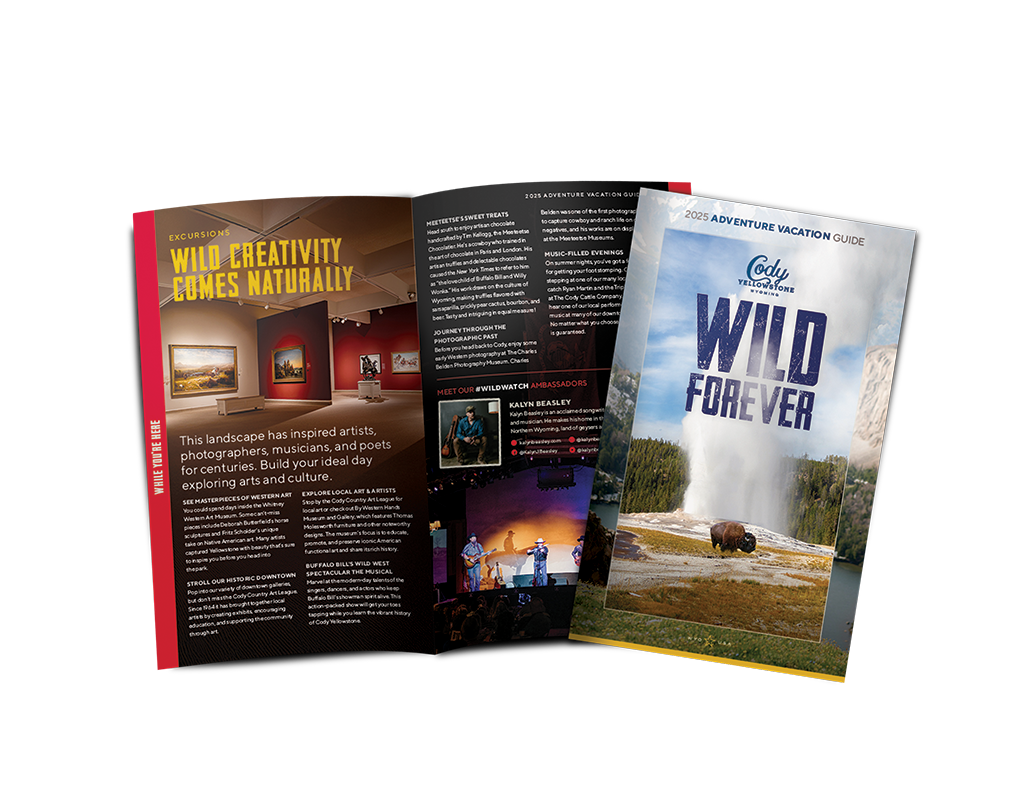

Get Your Free Cody Yellowstone Vacation Guide

Start planning your wild adventure with the help of our free guide.